Is safety management today more cult than culture?

Over the last three decades, the safety of the construction environment has improved dramatically. Yet, construction sites are still one of the most dangerous workplaces the world over. As a result, today’s safety management efforts are focused on ensuring that no amount of harm is considered acceptable on a construction site. This commitment to the “zero harm” standard is now regularly included on company logos, plastered across work site and is a mantra that has become a part of standard industry speak.

However, all of this focus on zero harm, and the approach that it entails, begs a few questions that very few people are asking:

- Are we actually making construction a safer place to work?

- Are safety statistics and field reporting becoming a more or less reliable source of information to improve the wellbeing of our people?

- Does it drive the behaviours and actions from our people that we intended?

- Are we bringing safety and our work methods closer together or are we driving them further apart?

- Are we making conversations about safer ways of doing work easier and more open, or are we creating a language of political correctness?

How can you question Zero Harm?

It might be suggested that questioning an approach that advocates zero harm is like arguing against education or child welfare – the counter-point is that you’re arguing for harm! You might be considered part of the backward thinking community that believes that construction is a dangerous place and s#@t happens! On the contrary, zero harm is a noble and appropriate aspiration – one that our improvement efforts should continuously strive to attain – but it is an aspiration not a standard by which people should be judged.

As a construction project manager for 20 years, there is nothing that weighed on me more than when some form of harm came to someone in my team or, for that matter, an incident occurred that only through good fortune didn’t result in injury or worse. It is for precisely this reason we should question, and continue to question, whether our improvement efforts are truly making a positive difference. As soon as we fall in line with default thinking, join the cult, we have become part of the problem rather than the solution.

But what’s the harm in Zero Harm?

The risk is that we are managing Zero Harm in the same way that so many other aspects of construction projects are managed – we believe performance is achieved through measurement and reporting. When the numbers show a negative variance to expectations then we find those responsible and hold them accountable. But if the standard is zero then any incident or reportable event is a negative occurrence.

We create a situation where people adjust their reporting to better match expectations so they avoid recriminations. We lose some of our ability to communicate openly and freely so that we can improve. A blame culture begins to erode some of the positive cultural gains we’ve made in safety over the last 10 or 15 years.

The systems and processes that were put in place to bring rigour to the management of risks and hazards become a tool for measurement and assessment. We begin to reduce these systems to the role of compliance documentation rather than a structured approach for truly thinking about where things might go wrong and how to stop it from happening.

These are not merely conceptual concerns. These are observations that come from spending months working with tradespeople, supervisors and site engineers as they went about their work on a daily basis.

How did construction safety get to where it is today?

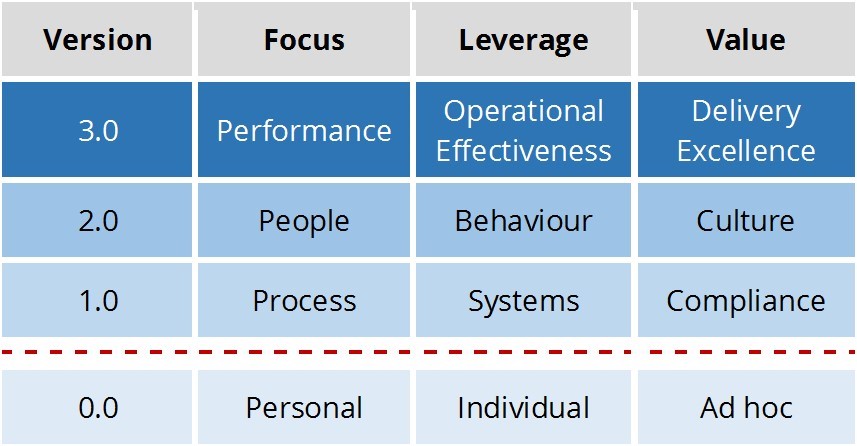

Figure 1 (below) provides a perspective on the evolution of construction safety management. It also provides as a glimpse into where I believe the next major shift in the safety of the construction workplace will come from.

Figure 1. The Evolution of Safety in Construction [1]

[1] Admittedly, this is a “first world” evolution – there are still many countries and industries that are quite low in the evolutionary process.

Prior to the 1980s, the focus in construction safety was personal. Leverage was limited to each individual’s experience looking out for themselves and managing the risks they could control. As a result, the management of safety risks and hazards was ad hoc and injuries were commonplace.

Fortunately, there was a growing movement that believed that this was neither acceptable nor the best that could be done. In the 1980s, certain industry sectors (most notably oil and gas) and some of the world’s larger economies began to expect a more rigorous and holistic approach to workplace safety. The focus was on process that leveraged management systems as a means of delivering this rigour on a consistent basis. However, their value was vested in compliance and relied heavily on surveillance and personal responsibility to be effective.

In the 2000s, it became clear that to achieve the level of improvement that government, owners, and now the industry were seeking, people needed to be the next point of focus as it was people that crafted these management systems, it was people that implemented the systems and it was people that executed the work that we were looking to make safer.

The key point of leverage was shifting behaviours and beliefs to view safety not as a procedural requirement but as a human imperative. We began to bring people-based conversations to bear on the challenges and issues that surround the creation of truly safe workplaces. Most importantly, safety was instilled as a value that was not to be compromised in the pursuit speed or cost efficiency. As a result, Safety 2.0 helped to create a strong cultural imperative to perform work safely.

The coming together of this cultural change along with the earlier elements of personal responsibility and processes and systems created another step change in the safety of the construction workplace. Certainly there are still pockets of resistance, but by humanising safety we have created a significant shift in our behaviours and beliefs about safety.

Delivery excellence will bring the next step change in safety

In spite of these improvements, construction is still one of the most unsafe places in which to work. This (rightly) means the industry is looking for the next step change – for Safety 3.0. Here the focus is on performance. There is an expectation that the previous evolutionary steps will start to work more effectively together and the performance metrics will not continue trending gently downward but dip sharply toward zero. Not only will the serious incidents and injuries fall away sharply but the minor injuries and incidents will as well. That the exceptions, the compromises and the outliers will be eliminated.

What is unarguable is that simply espousing Zero Harm will not result in a workplace where this major shift occurs. We actually have to DO things differently if we want to see this level of improvement. What we do must translate into changes in the way that our people go about their business every day. It can’t simply be a change in the way we talk every day.

To drive our safety performance toward the zero harm standard we need to stop isolating safety as something that is separate from executing work and focus on delivery performance in a holistic way. We need to ensure that safety is truly integral to the way we plan and execute construction work by getting better at planning and executing work. The leverage to do this is not measurement but operational effectiveness – bringing mastery to the way that work gets done every day.

5 ways to bring safety and delivery together as one

It is no coincidence that high performing teams have no problem creating a safe work environment. Safety, time, cost and quality performance are not trade-offs between competing priorities. They are results that are born of the same mother – delivery excellence.

If we are to drive the next step change in safety performance across all of our construction sites, we need to use techniques that will not only improve the safety of the working environment, but will also improve the overall efficiency and effectiveness from a time, cost and quality perspective.

- Value Creation in Design. Instead of making safety in design a “mandatory review” actually design a safe, efficient, effective installation process into the product. Do this by designing the installation process at the same time that the product is being designed. Make safety in design and constructability reviews an assessment of both the product and process design not just a review of whether this is a design you’re happy to build.

- Production Planning. Execution level planning not traditional scheduling allows you to ensure that every element of the job has been considered and that nothing is left to chance or missed out. This includes not only the activities that make up the construction work but also those activities that enable it (e.g., access, materials, permits, information, resources) and where it sits in the workflow.

- Production Control. Only start work once all the pre-requisites have been addressed and the team are able to complete it. This eliminates re-work that invariably gets done in suboptimal conditions and at greater risk (e.g., reduced access, less support, under operational conditions).

- 5S (sort, set in order, shine, standardise, sustain). Instead of making “housekeeping” a rubbish clearing activity that happens monthly when senior management or VIPs are visiting, make it a daily activity (or even at each daily break!) where you order the site to allow easy access and smooth workflow. Minimise your inventory of materials and equipment at the workfront to what’s need for the day and arrange them so they’re logistically and ergonomically easy to use.

- Continuous improvement. Use the data that a rigorous approach to operational effectiveness gives you to not only correct deficiencies but to identify and capitalise on opportunities. Do it as a proactive and consistent leadership activity and not as a means of punishing the guilty. Actively involve the people responsible for doing the work, not as a means of pointing out their shortcomings, but as a way of soliciting their firsthand knowledge and experience in making meaningful improvements.

To truly aspire to create a construction workplace where no one is harmed, we need to focus on being exceptional at every aspect of doing the work. The next step change in safety – Safety 3.0 – will come when we apply the best of Safety 1.0, the rigorous and structured approach, and the best cultural elements of Safety 2.0 to every aspect of how we deliver work every day. Results don’t come by focusing on the results – they come by helping our people be their very best. The results will come when we worry less about declaring our commitment to zero harm and begin to demonstrate that commitment by bringing excellence to every aspect of our delivery performance.

This is what will make construction businesses thrive. It will differentiate top-performers from the competition in the clients’ eyes. It will create the workplaces that make our people safe, as well as engage and motivate them to drive ever-greater levels of performance.

Questions for consideration

- Are your Zero Harm initiatives having the profound impact on the construction workplace that is required to eliminate harm?

- Are you empowering your people to create a safer workplace or disengaging them from the conversation?

- What are your people doing differently, day-in and day-out, to improve theirs and their co-workers’ safety?

I’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences in the comments below.

Well put.

I have thought for some years that safety has been dealt with in isolation from productivity. And that true lasting safety culture requires that productivity criteria be included in the safety protocols.

Because one thing is certain, and it happens on every site every day- if the declared ‘safe’ method doesn’t make sense, the people won’t use it!

I suspect that there are other reasons for all the regulations these days, and it is not to do with safety.

Any safety protocol that stubbornly marginalises productivity, common sense and human nature will eventually lead to a breech, or worse.

Productivity, culture and safety are three words in the one sentence.

Excellent observations! We can only hope that one day we’re less concerned with the perception of excellence and actually focus on being excellent. Thanks for the comments.